The Skin: Understanding The Largest Organ of the Body

October 4, 2016

On our last encounter we discussed wound bed preparation and the TIME framework. What I wish to accomplish with this post is to make it easier to understand the skin, the changes it undergoes as we age, and pave the way for the phases of wound healing—all of which are essential in becoming a better clinician.

In the assessment of wounds, we always ask ourselves questions such as: is the wound full- or partial-thickness? What structures are involved? Is that granulation tissue or epithelium? Is that the dermis, epidermis or hypodermis? All this information will assist with better documentation and increased awareness in determining the extent of tissue damage involved in a wound. Critical thinking will come naturally with a greater understanding of the skin's anatomy and the next thing you know, dressing selection and determining the type of wound and etiology will also become second nature.

What is the largest organ of the body?

Many people—and even clinicians—tend to forget about the largest organ of the body. Not only do we tend to forget at times, but we also fail to realize that like other organs, (e.g. heart, lungs, kidneys and liver), the largest organ of the body also sometimes fails. So why is it that the largest organ of the body is often also the most neglected?

Without further ado, in this corner: weighing in at approximately 12 pounds (5.5 kilos), 18 square feet in area (1.7 square meters) and slightly acidic with a pH range of 4.5-5.5 is, the SKIN (cheers and applause!).

What are the main functions of the skin, you ask? Well, I'm glad you did. The main functions of the skin are as follows: protection, water retention, thermoregulation, vitamin D synthesis, sensation and body image.

Layers of the Skin and Cells Involved

Now that we have an understanding of the importance of the largest organ of the body, its function and that it goes through changes as we age (and may even experience failure), let's breakdown the skin's anatomy.

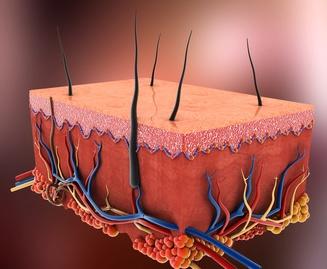

The skin is composed of three layers: the epidermis, the dermis and the subcutaneous layer also referred to as the hypodermis.

The Epidermis

The outermost and visible layer of the skin is the epidermis. The epidermis varies in thickness, has no blood supply of its own and is dependent of the dermis for nourishment and oxygen supply. It provides a waterproof barrier and also assists in creating our skin tone as melanocytes are present in the inner most layer of the epidermis. The epidermis is composed of five layers of stratified epithelium. The inner most layer cells (keratinocytes) are pushed upwards and eventually the dead cells are cast off with every day activity, such as showering. This process of the skin takes approximately 25-28 days. Minor injuries such as sunburns and minor abrasions affect this layer. Cells in the epidermis mostly include keratinocytes, melanocytes, Merkel and Langerhans cells. In between the epidermis and the dermis lies the basal membrane zone (BMZ), this is also referred to as the dermal-epidermal junction. The BMZ has rete ridges that anchor the epidermis to the dermis.

The Dermis

Up next is the dermis; the second layer of the skin. This layer is mostly made up of collagen and elastin fibers and is what provides strength, bulk, support and elasticity to the skin's tissue. There is a lot of anatomical magic happening here. The dermis is rich in nerve and blood supply and is divided into two layers; papillary and reticular dermis. The appendages present in this layer include sebaceous glands, sweat glands and hair follicles, as well as sensory and motor nerves that possess a rich blood supply. Partial-thickness wounds extend through the epidermis and into the dermis, where hair follicles and all other appendages are still present. These wounds heal through regeneration (secondary intention). Cells present in the dermis include mast cells, neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes.

The Hypodermis

Last but not least is the subcutaneous layer or hypodermis. When describing tissue damage, we know what type of injuries involve the first two layers, as damage extends through the epidermis, through the dermis, then we land in the hypodermis. The hypodermis lies right below the dermis and is the innermost layer of the skin. It is mainly composed of adipose and connective tissue. It is a receptacle for storage in the form of fat which stores nutrients and energy. Finally, it provides our body with insulation, shock absorption or cushioning, and support.

Quick Fun Fact: The skin is thinnest in the eyelids and thickest in the palms of hands and soles of feet.

Skin Changes as We Age

Not only will we be dealing with local and systemic barriers in wound management, but we also face the imminent changes of our skin as we age. As our bodies pass the sixth decade of life, the skin begins to experience delays in the wound healing process. There is a decrease in dermal thickness (thinner skin), collagen and elastin fibers, fatty layers (less protection), our rete ridges in the BMZ change in size and start to flatten out, and we experience changes in circulation, sensation and metabolism.

What does all this of this information about the skin mean and how does it relate to managing our patients' wounds? Having an understanding of the skin's structure allows us to appreciate the importance of collaboration in care and the SWAT team (skin, wound assessment team) in wound management. As wound clinicians, we are dealing with barriers such as diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, peripheral arterial occlusive disease, effects of medications, nutrition, hydration, mobility and continence, and on top of that, we must apply the skin changes as we age: delayed healing rates, less protection, less circulation, and increased incidence for pressure injuries. This makes us realize that we are really swimming against the current with our patients of advanced age.

Managing the body's largest organ makes us begin to realize that this job is just too big for us to take on without the support of the SWAT team, and a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approach to wound management. Communication with MD, PT, OT, ST, RT, nurse assistants, dietitians, hydration aides, medication aides and yes, our maintenance department too, are all important in delivering optimal care to our patients. You see, it is our responsibilities as clinicians to identify what our barriers to healing are, keep open our communications and provide our colleagues, patient, their family members and all of the SWAT team with the tools necessary to be successful for our common denominator…the patient.

Keep healing, my friends!

References:

Wound Care Certification – Study guide (J. Shah, P.J. Sheffield, C. Fife), ch. 3 anatomy of skin

The Wound Care Handbook 2nd edition – Medline Industries Inc., ch. 2 The Basics of Wound Care

About the Author

Martin Vera is a certified wound specialist with over 19 years of nursing experience, with a passion for wound management and patient-centered care.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely those of the author, and do not represent the views of WoundSource, HMP Global, its affiliates, or subsidiary companies.

Follow WoundSource

Tweets by WoundSource