How to Identify Pressure Injuries in Skin of Color

January 7, 2023

Introduction: A Case Study

A 55-year-old African American male was admitted to our inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) with a right trochanter stage 4 pressure injury, sacral stage 3, and left below the knee amputation (L BKA) with comorbid diabetes mellitus (DM) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD).  A 2-person skin assessment was completed on admission by 2 RNs, one of whom had worked in a wound clinic for several years. While changing his negative pressure wound therapy device on his right hip 1 week later, I decided to check his right heel.

A 2-person skin assessment was completed on admission by 2 RNs, one of whom had worked in a wound clinic for several years. While changing his negative pressure wound therapy device on his right hip 1 week later, I decided to check his right heel.

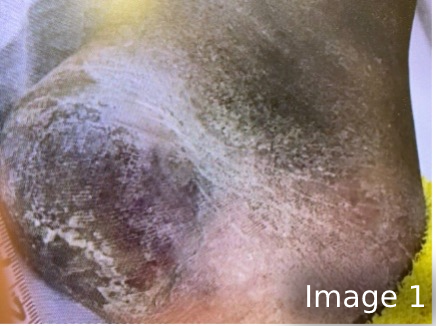

He had evidence of callus and ashy skin, but I thought I could see an injury curved around the callus area, as seen in image 1. Upon further inspection, I discovered a stage 2 blister approximately 4x5 cm. The skin had the texture of dry, crumpling, thin cardboard. He had no sense of pain in the area. As an amputee, he did not have another heel to compare temperature, texture, or color.

Pigmented Skin and Pressure Injuries

The National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel published new guidelines in 2020 on the assessment of skin of color to improve the capture of pressure injuries (PI)—especially stage 1 and unstageable pressure injuries.1 Of course, pain can be an indicator for sensate patients. Medium to darkly pigmented skin can be easily obscured in visual skin assessments due to the presence of callus, dry or ashy skin, and dim lights.2

In addition, dark skin does not blanch when pressure is applied over bony prominences. Improving our skills can capture these “hidden” tissue injuries. A well-lit room, the use of moisture for dry skin, and palpating for tenderness can help reveal these injuries. Rolling the patient to their side exposes the heel to light and for ease of palpation. While palpating, does the skin feel cooler or hotter than other areas; is it boggy or hardened? Darkly pigmented skin may not blanch or redden, but it will turn a purple, bluish, or eggplant color as the pressure injury develops. Remember that PIs cannot be staged from a photo, as nearly all indicators aren’t available in a photo.1-2

Don’t forget to also note any verbal reports from the patient, their family, or a previous facility’s medical record. One family informed me of a bruise on a patient’s nose under his glasses, which was present during his stay at a previous hospital. He did not want to lose them and wore them continuously for a few weeks, which may have led to the bruising.

What the Case Study Revealed

After I discovered the stage 2 blister on the patient’s right heel, the client and hospital staff became more diligent with offloading, using a podus boot in therapy and a soft boot in bed. Despite these efforts, the blister did rupture (Image 2) and the blistered skin macerated (Image 3). Per NPIAP guidelines, the blister was debrided to reveal a pink, viable, moist wound bed. No fat was visible as observable in Image 4. Our facility’s protocol indicated a collagen product would be the next course of action, in addition to continued offloading. By the time of the patient’s discharge from our facility, a dull pink layer of epithelium had partially covered the heel (Image 5).

After I discovered the stage 2 blister on the patient’s right heel, the client and hospital staff became more diligent with offloading, using a podus boot in therapy and a soft boot in bed. Despite these efforts, the blister did rupture (Image 2) and the blistered skin macerated (Image 3). Per NPIAP guidelines, the blister was debrided to reveal a pink, viable, moist wound bed. No fat was visible as observable in Image 4. Our facility’s protocol indicated a collagen product would be the next course of action, in addition to continued offloading. By the time of the patient’s discharge from our facility, a dull pink layer of epithelium had partially covered the heel (Image 5).

Lessons Learned

With the above case study in mind, I would recommend most to re-educate all nursing staff to assess skin of color properly. I would also recommend the use of soft offloading boots in bed for all patients with amputations to prevent the development of any PIs on their remaining foot. Always turn on and maximize lighting when performing assessments. Always turn the patient, when possible, to assess the heel in good light. Moisten when appropriate and palpate all at-risk areas, especially for skin of color on bony prominences, to achieve an assessment worthy of your patient. For more information on the differences between assessing skin of light and dark pigmentation, please see the following resource provided by the NPIAP: 6-NPIAP-Staging-Card.pdf (advancingexcellence.org)

References

- Haesler E. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. The International Guideline. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance; 2019.

- Bennett AM. Report of the Task Force on the Implications for Darkly Pigmented Intact Skin in the Prediction and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers. Adv Wound Care. 1995;8(6):34-35.

Suggested Reading

Black JM, Brindle CT, Honaker JS. Differential diagnosis of suspected deep tissue injury. Int Wound J. 2016;13(4):531-539.

About the Author

Janet Wolfson is a wound care and lymphedema educator with former ILWTI, and Lymphedema and Wound Care Coordinator at Health South of Ocala with over 30 years of field experience.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely those of the author, and do not represent the views of WoundSource, HMP Global, its affiliates, or subsidiary companies.

Follow WoundSource

Tweets by WoundSource