Caring for a Person With Problems of the Lower Leg: A Nurses Guide Toward Best Practice

February 22, 2022

Introduction

It is important for nurses to strive toward excellence. Our patients deserve the best we are able to give, and sometimes we need to look critically at how we care and how we might improve outcomes. In theory, we update practice because we read research that indicates a change needs to be incorporated into what we do. More often, maybe we follow a colleague and like what we see, or the patient indicates a preference and we change an approach. It may be that a company representative visits and what they say makes sense, has the support of management, and we gladly (or not) incorporate a product into our practice. Looking at a standard of practice and reflecting on how we measure up require honesty and an openness that some might shy away from. Such reflective practice, combined with clinical supervision, leads to high-quality care1 and is an excellent method of reviewing, updating, and improving practice for patients with problems of the lower leg.

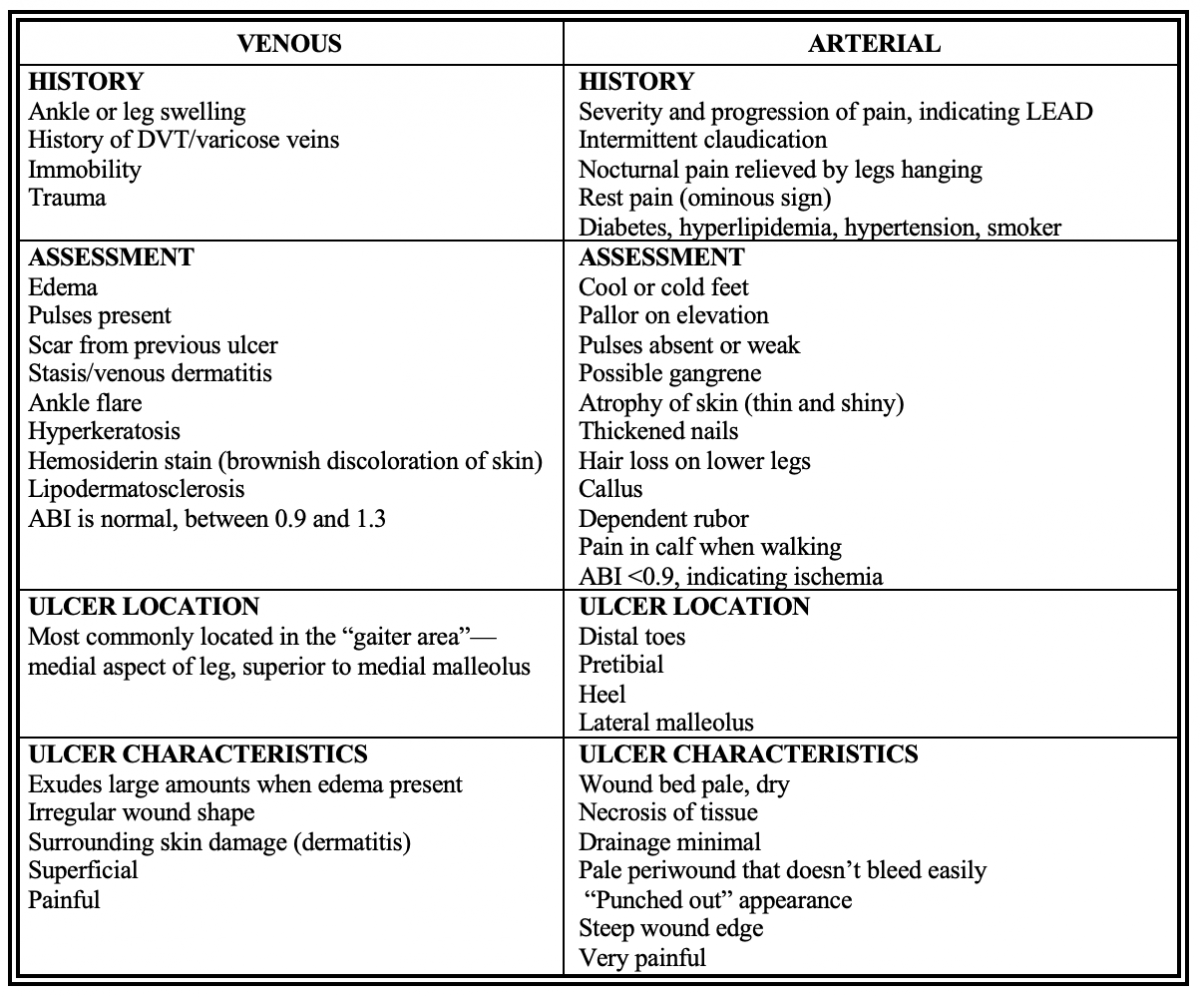

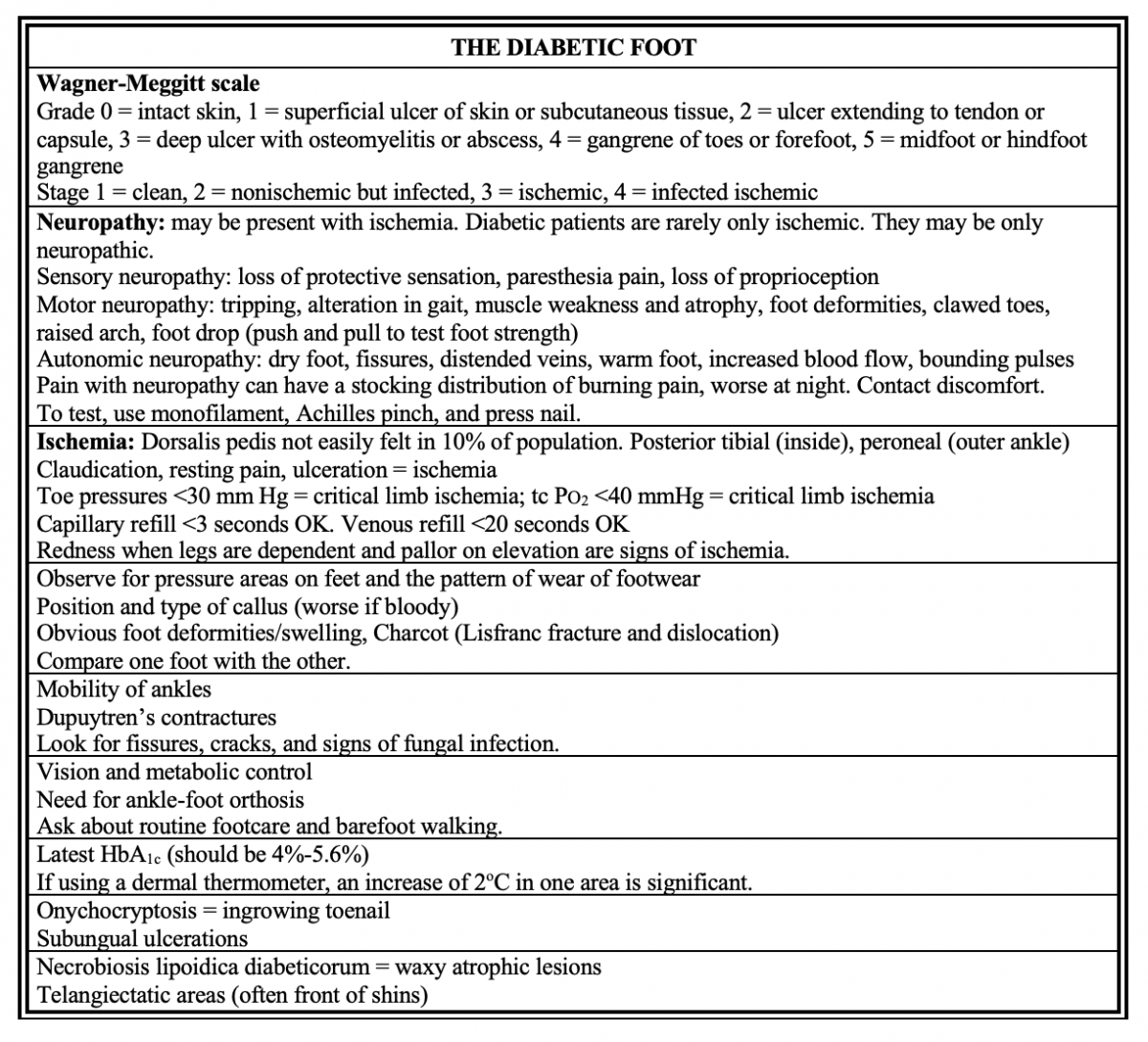

Fundamental to care is the process of assessment, and this is particularly important with the care of legs because differentiating among lower extremity venous disease (LEVD), lower extremity arterial disease (LEAD), and lower extremity neuropathic disease (LEND) is the key to a successful treatment plan and positive outcomes.2 Using a treatment plan that includes high compression wraps on a patient with an arterial ulcer may result in compromising the limb, so clearly nurses need to be confident and competent in this area. Mixed venous and arterial disease is not uncommon,3 and people with LEVD may also have congestive heart failure or pulmonary disease. Therefore, ongoing evaluation of any plan is important, as is looking at the whole person and not just the leg, wound, foot, or nails. The legs may also have issues relating to lymphedema, pressure, neurological problems, muscle wasting, skin problems, obesity, and trauma. The treatments may need to be specific, but care is more universal.

Differentiating LEVD, LEAD, and LEND

The help sheets found below are to assist with comprehensive assessment. It is important to assess both legs and to look at footwear. A history as well as any signs or symptoms being experienced should be discussed. Pedal pulses may be difficult to feel, and it is good to remember that people without palpable pulses may have a perfectly good arterial supply to the feet. Utilizing Doppler ultrasound to check both the dorsalis pedis and the posterior tibial arteries is helpful in deciding whether to refer for a more detailed vascular assessment.4

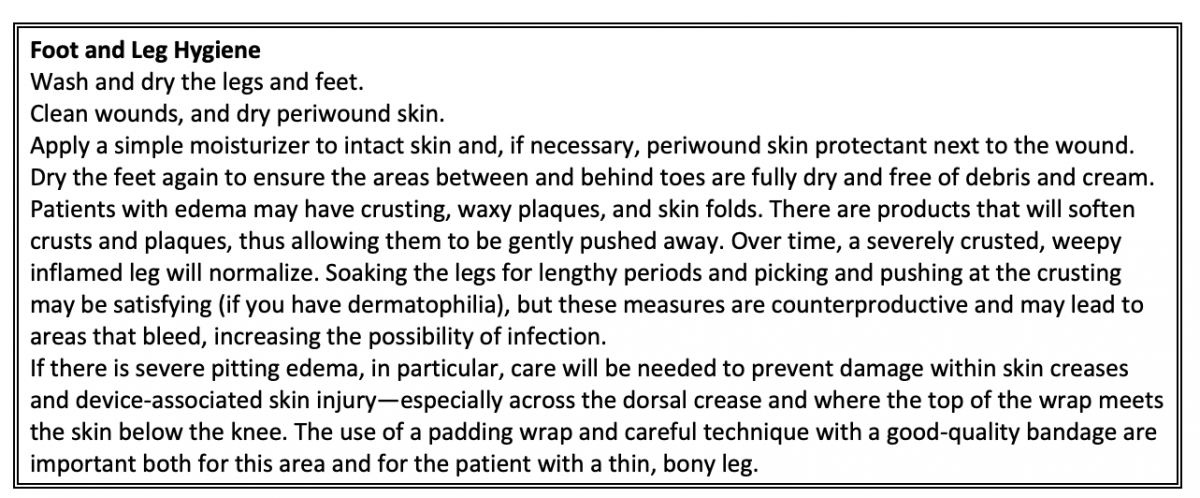

Note any skin conditions, such as shiny skin, hairless skin, dry and flaky skin, waxy plaques, or hard fibrosis. Skin color and the color and position of any patches, particularly hemosiderin staining ankle flare and telangiectasias, are important. The color of the leg when dependent and then raised needs to be assessed. Check for wounds between and behind toes, and then assess and measure them if found. Check the heels and bony prominences for pressure injuries. Assessing for the level of edema, lymphedema, or lipedema and differentiating among these conditions is necessary for long-term management. Essentially, edema is fluid within the tissues, lymphedema is engorged tissue secondary to high protein and lymphatic drainage dysfunction, and lipedema is abnormal fat distribution with an inflammatory component. If lymphedema is suspected, try to pinch a fold of skin at the base of the second toe on the top of the foot (Stemmer’s sign), and if it is not possible, lymphedema is indicated. Measure the legs because changes in the size of the limb allow tracking of improvement vs deterioration. The easiest way to measure a limb is at the smallest circumference around the mid-dorsum of the foot and above the malleolus and at the largest circumference around the calf below the tibial tuberosity. However, if there is a local policy, it is best to use that instead.

Ankle mobility can be reduced for many reasons: age-related joint problems, previous trauma, and lower extremity neuropathic disease. If neuropathic disease is suspected, a monofilament test can be done. Footwear and any orthotics or splints will need to be looked at, to check the fit and assess continued appropriate use. Pain can be severe with most lower extremity disease processes. Some say ischemic pain is the most severe and, of course, it is an emergency when combined with extreme pallor, indicating arterial occlusion. Where there is cellulitis and pain that is disproportionate to the size and visual severity of the wound, necrotizing fasciitis should be suspected. Vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and calciphylaxis are all associated with severe pain.

Although these conditions warrant acute interventions and pain management strategies, the pain associated with regular skin and wound care needs to be addressed with oral analgesia in conjunction with topical preparations and nonadherent dressings. It is common for patients with venous leg ulcers to experience severe stinging from some wound cleansers and dressings. Itching and scratching can also be problematic and severe, leading to removal of bandages and skin damage. It is considered a standard of care to have an ankle-brachial pressure index (ABI) performed if there is any indication of arterial disease or if high compression wraps are to be used.5 Toe pressure may be measured to check whether the blood supply to the toes is sufficient.

ABI, ankle-brachial index; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; LEAD, lower extremity arterial disease. Designed from a variety of sources. Help sheets are available on healewoundcare website 2022.  HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; tc PO2 transcutaneous oximetry. Designed from a variety of sources. Help sheets are available on healewoundcare website 2022.

HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; tc PO2 transcutaneous oximetry. Designed from a variety of sources. Help sheets are available on healewoundcare website 2022.

Care for the Lower Legs and Feet

Performing skin care only to the periwound is insufficient to maintain hygiene. As a visiting nurse, I once discovered a patient who had been in the hospital for over a week for an amputation of his leg. On assessing his remaining foot, I noticed long, curled nails cutting into his skin, debris between his toes, and a well-adhered dressing over the ball of his foot that, on removal, revealed a small, dry crater. He told me he had missed his podiatry visit because of his emergency surgery. Nursing is about better care than this. It needs to be comprehensive and complete. Managers have a responsibility to ensure there is time to perform care at a consistent, high standard.

Bandage/Wrap Styles

There are many different styles of bandages: short stretch, long stretch, elastic, conforming, cotton nonconforming, adhesive, sticky, foam, padding, two, three, four layer, high compression, and reduced compression. It is necessary to know what wrap is prescribed, which materials are currently used, and how to apply the wrap in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Rules for Wrapping

Remove wraps by unwrapping if possible. If scissors are to be used, free the skin and slide the fingers off to one side and ahead of the scissor blade. Take time to be very careful. Do not slide bandage scissors along the skin. This is very uncomfortable/painful and easily damages delicate skin. An easy way to demonstrate this procedure is to have someone cut a wrap off your leg. A narrow wrap exerts more pressure than a wider wrap.The larger the limb circumference, the less the pressure —hence, on a normally shaped leg there will be a gradual decrease in pressure between the ankle and the calf; giving graduated compression a higher level at the narrow ankle to a lower level at the larger circumference of the calf (this assumes that a consistent stretch is applied).The more layers of wrap and the more overlap there are, the more pressure there will be under the wrap. Increasing the tension (stretch) on the wrap increases the pressure it exerts.6

Figure 1

- Control is optimized by holding the wrap as shown (Figure 1) and working laterally to medially.

- Start at the base of the toes at the fifth metatarsal and go across the dorsum.

- If you start at the ankle, there will be a tourniquet effect, and the foot will swell. If there are concerns regarding ability to fit into shoes, minimize underlayers and padding—not the compression wrap.

- Secure the wrap with a full circle.

- Take the next circle to the bend of the planter surface of the heel with about a 50% overlap; on a larger foot another circle will be needed, hence the approximate overlap.

- Ensure the ankle is flexed to a 90-degree angle.

- The next circle will need to go centrally over the heel and dorsal crease to remain secure and keep the heel covered. Inclusion of the heel is important for the compression layer.

- Next go around the ankle low, close to the heel. This technique also helps to secure the heel cover. If a pleat forms, flatten it to one side or the other, not directly on the Achilles.

- Proceed up the leg at a 50% overlap (or as instructed) and with even tension.

- After covering the calf, let the tension off a little, making the next circle the last. If this last circle can be angled downward it can help to prevent slippage.

- Cut the wrap and secure with tape strips, but not circumferentially. If it is a sticky wrap, firmly press to optimize conformity and stickiness.

- Wraps on the lower leg should finish above the calf at the tibial tuberosity, two finger widths below the knee (Figure 2). The wrap should not reach into the popliteal space.

Figure 2

- Do not finish off the roll with extra circles above the calf because this equals a tourniquet (Laplace's law).

- It is safer to chevron rather than circle a limb or digit (Figure 3). This is because the crossover point of the chevron is more proximal and not at the same level, which avoids a tourniquet.

Figure 3

- Check that the toes are a good color and that the patient is comfortable in the wrap. Also check whether the patient can wriggle their warm toes (color, sensation, motion, temperature [CSMT] check).

- The patient needs to know the following:

- The schedule of leg elevation to offload the heel.

- If the leg becomes uncomfortable, they should elevate their leg and then remove the wrap if the pain worsens. Report the problem to the agency, clinic, or doctor as soon as practical.

- If they need to remove the wrap, it is best to unwrap and not use scissors to cut it off.

- If the patient has a history of congestive heart failure, inform them to remove the wraps if they become breathless.

- If using a sticky wrap, let the patient know it may be difficult to move in bed, as well as put on a shoe. Putting on an extralarge knee-high (thin nylon) stocking will allow the foot to slide easily into a shoe and stops the wrap from “catching.”

Conclusion

Lower leg management benefits from consistent high-quality care that begins with assessment. Regular, thorough skin care coupled with evaluation of the effectiveness of treatment ensures optimal progress. Patient and caregiver education develops ongoing strategies that minimize the possibility of complications and recurrence. All of these areas benefit from the attention to detail that comes with skilled nursing care that is maintained by clinical supervision and reflective practice.

References

- Snowdon DA, Hau R, Leggat SG, Taylor NF. Does clinical supervision of health professionals improve patient safety? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(4):447-455. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzw059

- Bonham PA, Flemister BG, Droste LR, et al. 2014 guideline for management of wounds in patients with lower-extremity arterial disease (LEAD): an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016;43(1):23-31. doi:10.1097/won.0000000000000193

- Marin JA, Woo KY. Clinical characteristics of mixed arteriovenous leg ulcers: a descriptive study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2017;44(1):41-47. doi:10.1097/won.0000000000000294

- Crawford PE, Fields-Varnado M. Guideline for the management of wounds in patients with lower-extremity neuropathic disease: an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40(1):34-45. doi:10.1097/WON.0b013e3182750161

- Kelechi TJ, Brunette G, Bonham PA, et al. 2019 guideline for management of wounds in patients with lower-extremity venous disease (LEVD): an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2020;47(2):97-110. doi:10.1097/won.0000000000000622

- Melhuish J, Clark M, Williams R, Harding K. The physics of sub-bandage pressure measurement. J Wound Care. 2000;9(7):308-310.

About the Author

Margaret Heale has a clinical consulting service, Heale Wound Care in Southeastern Vermont and draws on her extensive experience as a wound, ostomy and continence nurse in acute and long-term care settings to provide education and holistic care in her practice.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely those of the author, and do not represent the views of WoundSource, HMP Global, its affiliates, or subsidiary companies.

Follow WoundSource

Tweets by WoundSource